Scientific method refers to a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge.[1] To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry must be based on gathering observable, empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of reasoning.[2] The Oxford English Dictionary says that scientific method is: "a method of procedure that has characterized natural science since the 17th century, consisting in systematic observation, measurement, and experiment, and the formulation, testing, and modification of hypotheses."[3]

Although procedures vary from one field of inquiry to another, identifiable features distinguish scientific inquiry from other methods of obtaining knowledge. Scientific researchers propose hypotheses as explanations of phenomena, and design experimental studies to test these hypotheses. These steps must be repeatable, to predict future results. Theories that encompass wider domains of inquiry may bind many independently derived hypotheses together in a coherent, supportive structure. Theories, in turn, may help form new hypotheses or place groups of hypotheses into context.

Scientific inquiry is generally intended to be as objective as possible, to reduce biased interpretations of results. Another basic expectation is to document, archive and share all data and methodology so they are available for careful scrutiny by other scientists, giving them the opportunity to verify results by attempting to reproduce them. This practice, called full disclosure, also allows statistical measures of the reliability of these data to be established.

Contents[show] |

Introduction to scientific method

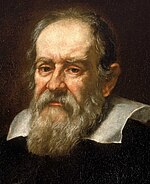

"Modern science owes its origins and present flourishing state to a new scientific method which was fashioned almost entirely by Galileo Galilei (1564-1642)" —Morris Kline[4] |

Johannes Kepler (1571–1630). "Kepler shows his keen logical sense in detailing the whole process by which he finally arrived at the true orbit. This is the greatest piece of Retroductive reasoning ever performed." —C. S. Peirce, circa 1896, on Kepler's reasoning through explanatory hypotheses[5] |

In the 20th century, a hypothetico-deductive model[8] for scientific method was formulated (for a more formal discussion, see below):

- 1. Use your experience: Consider the problem and try to make sense of it. Look for previous explanations. If this is a new problem to you, then move to step 2.

- 2. Form a conjecture: When nothing else is yet known, try to state an explanation, to someone else, or to your notebook.

- 3. Deduce a prediction from that explanation: If you assume 2 is true, what consequences follow?

- 4. Test: Look for the opposite of each consequence in order to disprove 2. It is a logical error to seek 3 directly as proof of 2. This error is called affirming the consequent.[9]

Note that this method can never absolutely verify (prove the truth of) 2. It can only falsify 2.[12] (This is what Einstein meant when he said, "No amount of experimentation can ever prove me right; a single experiment can prove me wrong."[13]) However, as pointed out by Carl Hempel (1905–1997) this simple view of scientific method is incomplete; the formulation of the conjecture might itself be the result of inductive reasoning. Thus the likelihood of the prior observation being true is statistical in nature [14] and would strictly require a Bayesian analysis. To overcome this uncertainty, experimental scientists must formulate a crucial experiment,[15] in order for it to corroborate a more likely hypothesis.

In the 20th century, Ludwik Fleck (1896–1961) and others argued that scientists need to consider their experiences more carefully, because their experience may be biased, and that they need to be more exact when describing their experiences.[16]

DNA example

Four basic elements of scientific method are illustrated below, by example from the discovery of the structure of DNA:

|

Truth and belief

Beliefs and biases

Needham's Science and Civilization in China uses the 'flying gallop' image as an example of observation bias:[24] In these types of images, the legs of a galloping horse are depicted as splayed, while the stop-action pictures of a horse's gallop by Eadweard Muybridge show otherwise. In a gallop, at the moment that no hoof is touching the ground, a horse's legs are gathered together and are not splayed. Earlier paintings depict the incorrect flying gallop observation.

This image demonstrates Ludwik Fleck's caution that people observe what they expect to observe, until shown otherwise; their beliefs will affect their observations (and, therefore, their subsequent actions, in a self-fulfilling prophecy). It is for this reason that scientific methodology prefers that hypotheses be tested in controlled conditions which can be reproduced by multiple researchers. With the scientific community's pursuit of experimental control and reproducibility, cognitive biases are diminished.

Certainty and myth

A scientific theory hinges on empirical findings, and remains subject to falsification if new evidence is presented. That is, no theory is ever considered certain. Theories very rarely result in vast changes in human understanding. Knowledge in science is gained by a gradual synthesis of information from different experiments, by various researchers, across different domains of science.[25] Theories vary in the extent to which they have been tested and retained, as well as their acceptance in the scientific community.In contrast, a myth may enjoy uncritical acceptance by members of a certain group.[26] The difference between a theory and a myth reflects a preference for a posteriori versus a priori knowledge. That is, theories become accepted by a scientific community as evidence for the theory is presented, and as presumptions that are inconsistent with the evidence are falsified.

Elements of scientific method

There are different ways of outlining the basic method used for scientific inquiry. The scientific community and philosophers of science generally agree on the following classification of method components. These methodological elements and organization of procedures tend to be more characteristic of natural sciences than social sciences. Nonetheless, the cycle of formulating hypotheses, testing and analyzing the results, and formulating new hypotheses, will resemble the cycle described below.- Four essential elements[27][28][29] of a scientific method[30] are iterations,[31][32] recursions,[33] interleavings, or orderings of the following:

- Characterizations (observations,[34] definitions, and measurements of the subject of inquiry)

- Hypotheses[35][36] (theoretical, hypothetical explanations of observations and measurements of the subject)[37]

- Predictions (reasoning including logical deduction[38] from the hypothesis or theory)

- Experiments[39] (tests of all of the above)

Scientific method is not a recipe: it requires intelligence, imagination, and creativity.[41] In this sense, it is not a mindless set of standards and procedures to follow, but is rather an ongoing cycle, constantly developing more useful, accurate and comprehensive models and methods. For example, when Einstein developed the Special and General Theories of Relativity, he did not in any way refute or discount Newton's Principia. On the contrary, if the astronomically large, the vanishingly small, and the extremely fast are reduced out from Einstein's theories — all phenomena that Newton could not have observed — Newton's equations remain. Einstein's theories are expansions and refinements of Newton's theories and, thus, increase our confidence in Newton's work.

A linearized, pragmatic scheme of the four points above is sometimes offered as a guideline for proceeding:[42]

- Define the question

- Gather information and resources (observe)

- Form hypothesis

- Perform experiment and collect data

- Analyze data

- Interpret data and draw conclusions that serve as a starting point for new hypothesis

- Publish results

- Retest (frequently done by other scientists)

While this schema outlines a typical hypothesis/testing method,[43] it should also be noted that a number of philosophers, historians and sociologists of science (perhaps most notably Paul Feyerabend) claim that such descriptions of scientific method have little relation to the ways science is actually practiced.

The "operational" paradigm combines the concepts of operational definition, instrumentalism, and utility:

The essential elements of a scientific method are operations, observations, models, and a utility function for evaluating models.[44][not in citation given]

- Operation - Some action done to the system being investigated

- Observation - What happens when the operation is done to the system

- Model - A fact, hypothesis, theory, or the phenomenon itself at a certain moment

- Utility Function - A measure of the usefulness of the model to explain, predict, and control, and of the cost of use of it. One of the elements of any scientific utility function is the refutability of the model. Another is its simplicity, on the Principle of Parsimony also known as Occam's Razor.

Characterizations

Scientific method depends upon increasingly sophisticated characterizations of the subjects of investigation. (The subjects can also be called unsolved problems or the unknowns.) For example, Benjamin Franklin correctly characterized St. Elmo's fire as electrical in nature, but it has taken a long series of experiments and theory to establish this. While seeking the pertinent properties of the subjects, this careful thought may also entail some definitions and observations; the observations often demand careful measurements and/or counting.The systematic, careful collection of measurements or counts of relevant quantities is often the critical difference between pseudo-sciences, such as alchemy, and a science, such as chemistry or biology. Scientific measurements taken are usually tabulated, graphed, or mapped, and statistical manipulations, such as correlation and regression, performed on them. The measurements might be made in a controlled setting, such as a laboratory, or made on more or less inaccessible or unmanipulatable objects such as stars or human populations. The measurements often require specialized scientific instruments such as thermometers, spectroscopes, or voltmeters, and the progress of a scientific field is usually intimately tied to their invention and development.

| "I am not accustomed to saying anything with certainty after only one or two observations."—Andreas Vesalius (1546) [45] |

Uncertainty

Measurements in scientific work are also usually accompanied by estimates of their uncertainty. The uncertainty is often estimated by making repeated measurements of the desired quantity. Uncertainties may also be calculated by consideration of the uncertainties of the individual underlying quantities that are used. Counts of things, such as the number of people in a nation at a particular time, may also have an uncertainty due to limitations of the method used. Counts may only represent a sample of desired quantities, with an uncertainty that depends upon the sampling method used and the number of samples taken.Definition

Measurements demand the use of operational definitions of relevant quantities. That is, a scientific quantity is described or defined by how it is measured, as opposed to some more vague, inexact or "idealized" definition. For example, electrical current, measured in amperes, may be operationally defined in terms of the mass of silver deposited in a certain time on an electrode in an electrochemical device that is described in some detail. The operational definition of a thing often relies on comparisons with standards: the operational definition of "mass" ultimately relies on the use of an artifact, such as a certain kilogram of platinum-iridium kept in a laboratory in France.The scientific definition of a term sometimes differs substantially from its natural language usage. For example, mass and weight overlap in meaning in common discourse, but have distinct meanings in mechanics. Scientific quantities are often characterized by their units of measure which can later be described in terms of conventional physical units when communicating the work.

New theories sometimes arise upon realizing that certain terms had not previously been sufficiently clearly defined. For example, Albert Einstein's first paper on relativity begins by defining simultaneity and the means for determining length. These ideas were skipped over by Isaac Newton with, "I do not define time, space, place and motion, as being well known to all." Einstein's paper then demonstrates that they (viz., absolute time and length independent of motion) were approximations. Francis Crick cautions us that when characterizing a subject, however, it can be premature to define something when it remains ill-understood.[46] In Crick's study of consciousness, he actually found it easier to study awareness in the visual system, rather than to study free will, for example. His cautionary example was the gene; the gene was much more poorly understood before Watson and Crick's pioneering discovery of the structure of DNA; it would have been counterproductive to spend much time on the definition of the gene, before them.

Example of characterizations

DNA-characterizations

The history of the discovery of the structure of DNA is a classic example of the elements of scientific method: in 1950 it was known that genetic inheritance had a mathematical description, starting with the studies of Gregor Mendel. But the mechanism of the gene was unclear. Researchers in Bragg's laboratory at Cambridge University made X-ray diffraction pictures of various molecules, starting with crystals of salt, and proceeding to more complicated substances. Using clues which were painstakingly assembled over the course of decades, beginning with its chemical composition, it was determined that it should be possible to characterize the physical structure of DNA, and the X-ray images would be the vehicle.[47] ..2. DNA-hypothesesPrecession of Mercury

The characterization element can require extended and extensive study, even centuries. It took thousands of years of measurements, from the Chaldean, Indian, Persian, Greek, Arabic and European astronomers, to record the motion of planet Earth. Newton was able to condense these measurements into consequences of his laws of motion. But the perihelion of the planet Mercury's orbit exhibits a precession that is not fully explained by Newton's laws of motion (see diagram to the right). The observed difference for Mercury's precession between Newtonian theory and relativistic theory (approximately 43 arc-seconds per century), was one of the things that occurred to Einstein as a possible early test of his theory of General Relativity.Hypothesis development

Normally hypotheses have the form of a mathematical model. Sometimes, but not always, they can also be formulated as existential statements, stating that some particular instance of the phenomenon being studied has some characteristic and causal explanations, which have the general form of universal statements, stating that every instance of the phenomenon has a particular characteristic.

Scientists are free to use whatever resources they have — their own creativity, ideas from other fields, induction, Bayesian inference, and so on — to imagine possible explanations for a phenomenon under study. Charles Sanders Peirce, borrowing a page from Aristotle (Prior Analytics, 2.25) described the incipient stages of inquiry, instigated by the "irritation of doubt" to venture a plausible guess, as abductive reasoning. The history of science is filled with stories of scientists claiming a "flash of inspiration", or a hunch, which then motivated them to look for evidence to support or refute their idea. Michael Polanyi made such creativity the centerpiece of his discussion of methodology.

William Glen observes that

- the success of a hypothesis, or its service to science, lies not simply in its perceived "truth", or power to displace, subsume or reduce a predecessor idea, but perhaps more in its ability to stimulate the research that will illuminate … bald suppositions and areas of vagueness.[48]

DNA-hypotheses

Linus Pauling proposed that DNA might be a triple helix.[49] This hypothesis was also considered by Francis Crick and James D. Watson but discarded. When Watson and Crick learned of Pauling's hypothesis, they understood from existing data that Pauling was wrong[50] and that Pauling would soon admit his difficulties with that structure. So, the race was on to figure out the correct structure (except that Pauling did not realize at the time that he was in a race—see section on "DNA-predictions" below)Predictions from the hypothesis

It is essential that the outcome be currently unknown. Only in this case does the eventuation increase the probability that the hypothesis be true. If the outcome is already known, it's called a consequence and should have already been considered while formulating the hypothesis.

If the predictions are not accessible by observation or experience, the hypothesis is not yet useful for the method, and must wait for others who might come afterward, and perhaps rekindle its line of reasoning. For example, a new technology or theory might make the necessary experiments feasible.

DNA-predictions

James D. Watson, Francis Crick, and others hypothesized that DNA had a helical structure. This implied that DNA's X-ray diffraction pattern would be 'x shaped'.[51][52] This prediction followed from the work of Cochran, Crick and Vand[19] (and independently by Stokes). The Cochran-Crick-Vand-Stokes theorem provided a mathematical explanation for the empirical observation that diffraction from helical structures produces x shaped patterns.Also in their first paper, Watson and Crick predicted that the double helix structure provided a simple mechanism for DNA replication, writing "It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material".[53] ..4. DNA-experiments

General relativity

Einstein's theory of General Relativity makes several specific predictions about the observable structure of space-time, such as a prediction that light bends in a gravitational field and that the amount of bending depends in a precise way on the strength of that gravitational field. Arthur Eddington's observations made during a 1919 solar eclipse supported General Relativity rather than Newtonian gravitation.[54]Experiments

Depending on the predictions, the experiments can have different shapes. It could be a classical experiment in a laboratory setting, a double-blind study or an archaeological excavation. Even taking a plane from New York to Paris is an experiment which tests the aerodynamical hypotheses used for constructing the plane.

Scientists assume an attitude of openness and accountability on the part of those conducting an experiment. Detailed record keeping is essential, to aid in recording and reporting on the experimental results, and providing evidence of the effectiveness and integrity of the procedure. They will also assist in reproducing the experimental results. Traces of this tradition can be seen in the work of Hipparchus (190-120 BCE), when determining a value for the precession of the Earth, while controlled experiments can be seen in the works of Muslim scientists such as Jābir ibn Hayyān (721-815 CE), al-Battani (853–929) and Alhacen (965-1039).

DNA-experiments

Watson and Crick showed an initial (and incorrect) proposal for the structure of DNA to a team from Kings College - Rosalind Franklin, Maurice Wilkins, and Raymond Gosling. Franklin immediately spotted the flaws which concerned the water content. Later Watson saw Franklin's detailed X-ray diffraction images which showed an X-shape and confirmed that the structure was helical.[20][56] This rekindled Watson and Crick's model building and led to the correct structure. ..1. DNA-characterizationsEvaluation and improvement

The scientific process is iterative. At any stage it is possible to refine its accuracy and precision, so that some consideration will lead the scientist to repeat an earlier part of the process. Failure to develop an interesting hypothesis may lead a scientist to re-define the subject they are considering. Failure of a hypothesis to produce interesting and testable predictions may lead to reconsideration of the hypothesis or of the definition of the subject. Failure of the experiment to produce interesting results may lead the scientist to reconsidering the experimental method, the hypothesis or the definition of the subject.Other scientists may start their own research and enter the process at any stage. They might adopt the characterization and formulate their own hypothesis, or they might adopt the hypothesis and deduce their own predictions. Often the experiment is not done by the person who made the prediction and the characterization is based on experiments done by someone else. Published results of experiments can also serve as a hypothesis predicting their own reproducibility.

DNA-iterations

After considerable fruitless experimentation, being discouraged by their superior from continuing, and numerous false starts,[57][58][59] Watson and Crick were able to infer the essential structure of DNA by concrete modeling of the physical shapes of the nucleotides which comprise it.[21][60] They were guided by the bond lengths which had been deduced by Linus Pauling and by Rosalind Franklin's X-ray diffraction images. ..DNA ExampleConfirmation

Science is a social enterprise, and scientific work tends to be accepted by the community when it has been confirmed. Crucially, experimental and theoretical results must be reproduced by others within the scientific community. Researchers have given their lives for this vision; Georg Wilhelm Richmann was killed by ball lightning (1753) when attempting to replicate the 1752 kite-flying experiment of Benjamin Franklin.[61]To protect against bad science and fraudulent data, governmental research-granting agencies such as the National Science Foundation, and science journals including Nature and Science, have a policy that researchers must archive their data and methods so other researchers can access it, test the data and methods and build on the research that has gone before. Scientific data archiving can be done at a number of national archives in the U.S. or in the World Data Center.

Models of scientific inquiry

Classical model

The classical model of scientific inquiry derives from Aristotle,[62] who distinguished the forms of approximate and exact reasoning, set out the threefold scheme of abductive, deductive, and inductive inference, and also treated the compound forms such as reasoning by analogy.Pragmatic model

- The method of tenacity (policy of sticking to initial belief) — which brings comforts and decisiveness but leads to trying to ignore contrary information and others' views as if truth were intrinsically private, not public. It goes against the social impulse and easily falters since one may well notice when another's opinion is as good as one's own initial opinion. Its successes can shine but tend to be transitory.

- The method of authority — which overcomes disagreements but sometimes brutally. Its successes can be majestic and long-lived, but it cannot operate thoroughly enough to suppress doubts indefinitely, especially when people learn of other societies present and past.

- The method of congruity or the a priori or the dilettante or "what is agreeable to reason" — which promotes conformity less brutally but depends on taste and fashion in paradigms and can go in circles over time, along with barren disputation. It is more intellectual and respectable but, like the first two methods, sustains capricious and accidental beliefs, destining some minds to doubts.

- The scientific method — the method wherein inquiry regards itself as fallible and purposely tests itself and criticizes, corrects, and improves itself.

For Peirce, rational inquiry implies presuppositions about truth and the real; to reason is to presuppose (and at least to hope), as a principle of the reasoner's self-regulation, that the real is discoverable and independent of our vagaries of opinion. In that vein he defined truth as the correspondence of a sign (in particular, a proposition) to its object and, pragmatically, not as actual consensus of some definite, finite community (such that to inquire would be to poll the experts), but instead as that final opinion which all investigators would reach sooner or later but still inevitably, if they were to push investigation far enough, even when they start from different points.[68] In tandem he defined the real as a true sign's object (be that object a possibility or quality, or an actuality or brute fact, or a necessity or norm or law), which is what it is independently of any finite community's opinion and, pragmatically, depends only on the final opinion destined in a sufficient investigation. That is a destination as far, or near, as the truth itself to you or me or the given finite community. Thus his theory of inquiry boils down to "Do the science." Those conceptions of truth and the real involve the idea of a community both without definite limits (and thus potentially self-correcting as far as needed) and capable of definite increase of knowledge.[69] As inference, "logic is rooted in the social principle" since it depends on a standpoint that is, in a sense, unlimited.[70]

Paying special attention to the generation of explanations, Peirce outlined scientific method as a coordination of three kinds of inference in a purposeful cycle aimed at settling doubts, as follows:[71]

1. Abduction (or retroduction). Guessing, inference to explanatory hypotheses for selection of those best worth trying. From abduction, Peirce distinguishes induction as inferring, on the basis of tests, the proportion of truth in the hypothesis. Every inquiry, whether into ideas, brute facts, or norms and laws, arises from surprising observations in one or more of those realms (and for example at any stage of an inquiry already underway). All explanatory content of theories comes from abduction, which guesses a new or outside idea so as to account in a simple, economical way for a surprising or complicative phenomenon. Oftenest, even a well-prepared mind guesses wrong. But the modicum of success of our guesses far exceeds that of sheer luck and seems born of attunement to nature by instincts developed or inherent, especially insofar as best guesses are optimally plausible and simple in the sense, said Peirce, of the "facile and natural", as by Galileo's natural light of reason and as distinct from "logical simplicity". Abduction is the most fertile but least secure mode of inference. Its general rationale is inductive: it succeeds often enough and, without it, there is no hope of sufficiently expediting inquiry (often multi-generational) toward new truths.[72] Coordinative method leads from abducing a plausible hypothesis to judging it for its testability[73] and for how its trial would economize inquiry itself.[74] Peirce calls his pragmatism "the logic of abduction".[75] His pragmatic maxim is: "Consider what effects that might conceivably have practical bearings you conceive the objects of your conception to have. Then, your conception of those effects is the whole of your conception of the object".[68] His pragmatism is a method of reducing conceptual confusions fruitfully by equating the meaning of any conception with the conceivable practical implications of its object's conceived effects — a method of experimentational mental reflection hospitable to forming hypotheses and conducive to testing them. It favors efficiency. The hypothesis, being insecure, needs to have practical implications leading at least to mental tests and, in science, lending themselves to scientific tests. A simple but unlikely guess, if uncostly to test for falsity, may belong first in line for testing. A guess's objective probability recommends it as worth testing, while subjective likelihood can be misleading. Guesses can be chosen for trial strategically, for which Peirce gave as example the game of Twenty Questions.[76] One can hope to discover only that which time would reveal through a learner's sufficient experience anyway, so the point is to expedite it; the economy of research is what demands the "leap" of abduction and governs its art.[74]

2. Deduction. Analysis of hypothesis and deduction of its consequences (for induction to test so as to evaluate the hypothesis). Two stages:

- i. Explication. Logical analysis of the hypothesis in order to render its parts as clear as possible.

- ii. Demonstration (or deductive argumentation). Deduction of hypothesis's consequence. Corollarial or, if needed, Theorematic.

- i. Classification. Classing objects of experience under general ideas.

- ii. Probation (or direct Inductive Argumentation): Crude (the enumeration of instances) or Gradual (new estimate of proportion of truth in the hypothesis after each test). Gradual Induction is Qualitative or Quantitative; if Quantitative, then dependent on measurements, or on statistics, or on countings.

- iii. Sentential Induction. "...which, by Inductive reasonings, appraises the different Probations singly, then their combinations, then makes self-appraisal of these very appraisals themselves, and passes final judgment on the whole result".[71]

Computational approaches

Many subspecialties of applied logic and computer science, such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, computational learning theory, inferential statistics, and knowledge representation, are concerned with setting out computational, logical, and statistical frameworks for the various types of inference involved in scientific inquiry. In particular, they contribute hypothesis formation, logical deduction, and empirical testing. Some of these applications draw on measures of complexity from algorithmic information theory to guide the making of predictions from prior distributions of experience, for example, see the complexity measure called the speed prior from which a computable strategy for optimal inductive reasoning can be derived.Communication and community

Frequently a scientific method is employed not only by a single person, but also by several people cooperating directly or indirectly. Such cooperation can be regarded as one of the defining elements of a scientific community. Various techniques have been developed to ensure the integrity of that scientific method within such an environment.Peer review evaluation

Scientific journals use a process of peer review, in which scientists' manuscripts are submitted by editors of scientific journals to (usually one to three) fellow (usually anonymous) scientists familiar with the field for evaluation. The referees may or may not recommend publication, publication with suggested modifications, or, sometimes, publication in another journal. This serves to keep the scientific literature free of unscientific or pseudoscientific work, to help cut down on obvious errors, and generally otherwise to improve the quality of the material.Documentation and replication

Archiving

As a result, researchers are expected to practice scientific data archiving in compliance with the policies of government funding agencies and scientific journals. Detailed records of their experimental procedures, raw data, statistical analyses and source code are preserved in order to provide evidence of the effectiveness and integrity of the procedure and assist in reproduction. These procedural records may also assist in the conception of new experiments to test the hypothesis, and may prove useful to engineers who might examine the potential practical applications of a discovery.Data sharing

When additional information is needed before a study can be reproduced, the author of the study is expected to provide it promptly. If the author refuses to share data, appeals can be made to the journal editors who published the study or to the institution which funded the research.Limitations

Since it is impossible for a scientist to record everything that took place in an experiment, facts selected for their apparent relevance are reported. This may lead, unavoidably, to problems later if some supposedly irrelevant feature is questioned. For example, Heinrich Hertz did not report the size of the room used to test Maxwell's equations, which later turned out to account for a small deviation in the results. The problem is that parts of the theory itself need to be assumed in order to select and report the experimental conditions. The observations are hence sometimes described as being 'theory-laden'.Dimensions of practice

- Publication, i.e. Peer review

- Resources (mostly funding)

Both of these constraints indirectly bring in a scientific method — work that too obviously violates the constraints will be difficult to publish and difficult to get funded. Journals do not require submitted papers to conform to anything more specific than "good scientific practice" and this is mostly enforced by peer review. Originality, importance and interest are more important - see for example the author guidelines for Nature.

Philosophy and sociology of science

Thomas Samuel Kuhn examined the history of science in his The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, and found that the actual method used by scientists differed dramatically from the then-espoused method. His observations of science practice are essentially sociological and do not speak to how science is or can be practiced in other times and other cultures.

Imre Lakatos and Thomas Kuhn have done extensive work on the "theory laden" character of observation. Kuhn (1961) said the scientist generally has a theory in mind before designing and undertaking experiments so as to make empirical observations, and that the "route from theory to measurement can almost never be traveled backward". This implies that the way in which theory is tested is dictated by the nature of the theory itself, which led Kuhn (1961, p. 166) to argue that "once it has been adopted by a profession ... no theory is recognized to be testable by any quantitative tests that it has not already passed".[78]

Paul Feyerabend similarly examined the history of science, and was led to deny that science is genuinely a methodological process. In his book Against Method he argues that scientific progress is not the result of applying any particular method. In essence, he says that for any specific method or norm of science, one can find a historic episode where violating it has contributed to the progress of science. Thus, if believers in a scientific method wish to express a single universally valid rule, Feyerabend jokingly suggests, it should be 'anything goes'.[79] Criticisms such as his led to the strong programme, a radical approach to the sociology of science.

In his 1958 book, Personal Knowledge, chemist and philosopher Michael Polanyi (1891–1976) criticized the common view that the scientific method is purely objective and generates objective knowledge. Polanyi cast this view as a misunderstanding of the scientific method and of the nature of scientific inquiry, generally. He argued that scientists do and must follow personal passions in appraising facts and in determining which scientific questions to investigate. He concluded that a structure of liberty is essential for the advancement of science - that the freedom to pursue science for its own sake is a prerequisite for the production of knowledge through peer review and the scientific method.

The postmodernist critiques of science have themselves been the subject of intense controversy. This ongoing debate, known as the science wars, is the result of conflicting values and assumptions between the postmodernist and realist camps. Whereas postmodernists assert that scientific knowledge is simply another discourse (note that this term has special meaning in this context) and not representative of any form of fundamental truth, realists in the scientific community maintain that scientific knowledge does reveal real and fundamental truths about reality. Many books have been written by scientists which take on this problem and challenge the assertions of the postmodernists while defending science as a legitimate method of deriving truth.[80]

Luck and science

Psychologist Kevin Dunbar says the process of discovery often starts with researchers finding bugs in their experiments. These unexpected results lead researchers to try and fix what they think is an error in their methodology. Eventually, the researcher decides the error is too persistent and systematic to be a coincidence. The highly controlled, cautious and curious aspects of the scientific method are thus what make it well suited for identifying such persistent systematic errors. At this point, the researcher will begin to think of theoretical explanations for the error, often seeking the help of colleagues across different domains of expertise.[81][84]

History

There are hints of experimental methods from the Classical world (e.g., those reported by Archimedes in a report recovered early in the 20th century CE from an overwritten manuscript), but the first clear instances of an experimental scientific method seem to have been developed in the Arabic world, by Muslim scientists (See Alhazen),[88] who introduced the use of experimentation and quantification to distinguish between competing scientific theories set within a generally empirical orientation, perhaps by Alhazen in his optical experiments reported in his Book of Optics (1021).[89][unreliable source?] The modern scientific method crystallized no later than in the 17th and 18th centuries. In his work Novum Organum (1620) — a reference to Aristotle's Organon — Francis Bacon outlined a new system of logic to improve upon the old philosophical process of syllogism.[90] Then, in 1637, René Descartes established the framework for a scientific method's guiding principles in his treatise, Discourse on Method. The writings of Alhazen, Bacon and Descartes are considered critical in the historical development of the modern scientific method, as are those of John Stuart Mill.[91]

In the late 19th century, Charles Sanders Peirce proposed a schema that would turn out to have considerable influence in the development of current scientific method generally. Peirce accelerated the progress on several fronts. Firstly, speaking in broader context in "How to Make Our Ideas Clear" (1878), Peirce outlined an objectively verifiable method to test the truth of putative knowledge on a way that goes beyond mere foundational alternatives, focusing upon both deduction and induction. He thus placed induction and deduction in a complementary rather than competitive context (the latter of which had been the primary trend at least since David Hume, who wrote in the mid-to-late 18th century). Secondly, and of more direct importance to modern method, Peirce put forth the basic schema for hypothesis/testing that continues to prevail today. Extracting the theory of inquiry from its raw materials in classical logic, he refined it in parallel with the early development of symbolic logic to address the then-current problems in scientific reasoning. Peirce examined and articulated the three fundamental modes of reasoning that, as discussed above in this article, play a role in inquiry today, the processes that are currently known as abductive, deductive, and inductive inference. Thirdly, he played a major role in the progress of symbolic logic itself — indeed this was his primary specialty.

Beginning in the 1930s, Karl Popper argued that there is no such thing as inductive reasoning.[92] All inferences ever made, including in science, are purely[93] deductive according to this view. Accordingly, he claimed that the empirical character of science has nothing to do with induction—but with the deductive property of falsifiability that scientific hypotheses have. Contrasting his views with inductivism and positivism, he even denied the existence of scientific method: "(1) There is no method of discovering a scientific theory (2) There is no method for ascertaining the truth of a scientific hypothesis, i.e., no method of verification; (3) There is no method for ascertaining whether a hypothesis is 'probable', or probably true".[94] Instead, he held that there is only one universal method, a method not particular to science: The negative method of criticism, or colloquially termed trial and error. It covers not only all products of the human mind, including science, mathematics, philosophy, art and so on, but also the evolution of life. Following Peirce and others, Popper argued that science is fallible and has no authority.[94] In contrast to empiricist-inductivist views, he welcomed metaphysics and philosophical discussion and even gave qualified support to myths[95] and pseudosciences.[96] Popper's view has become known as critical rationalism.

Relationship with mathematics

Science is the process of gathering, comparing, and evaluating proposed models against observables. A model can be a simulation, mathematical or chemical formula, or set of proposed steps. Science is like mathematics in that researchers in both disciplines can clearly distinguish what is known from what is unknown at each stage of discovery. Models, in both science and mathematics, need to be internally consistent and also ought to be falsifiable (capable of disproof). In mathematics, a statement need not yet be proven; at such a stage, that statement would be called a conjecture. But when a statement has attained mathematical proof, that statement gains a kind of immortality which is highly prized by mathematicians, and for which some mathematicians devote their lives.[97]Mathematical work and scientific work can inspire each other.[98] For example, the technical concept of time arose in science, and timelessness was a hallmark of a mathematical topic. But today, the Poincaré conjecture has been proven using time as a mathematical concept in which objects can flow (see Ricci flow).

Nevertheless, the connection between mathematics and reality (and so science to the extent it describes reality) remains obscure. Eugene Wigner's paper, The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences, is a very well-known account of the issue from a Nobel Prize physicist. In fact, some observers (including some well known mathematicians such as Gregory Chaitin, and others such as Lakoff and Núñez) have suggested that mathematics is the result of practitioner bias and human limitation (including cultural ones), somewhat like the post-modernist view of science.

George Pólya's work on problem solving,[99] the construction of mathematical proofs, and heuristic[100][101] show that the mathematical method and the scientific method differ in detail, while nevertheless resembling each other in using iterative or recursive steps.

Pappus,[102] involves free and heuristic construction of plausible arguments, working backward from the goal, and devising a plan for constructing the proof; synthesis is the strict Euclidean exposition of step-by-step details[103] of the proof; review involves reconsidering and re-examining the result and the path taken to it.

Gauss, when asked how he came about his theorems, once replied "durch planmässiges Tattonieren" (through systematic palpable experimentation).[104]

Imre Lakatos argued that mathematicians actually use contradiction, criticism and revision as principles for improving their work.[105]

0 comments:

Post a Comment